Dr. Stephen Holmes ist Mitgründer von idm, Trainer für interkulturelle Kommunikation und Diversity Management, Coach und freier Dozent. Zurzeit unterrichtet er zum Thema "Culture and Organization" für die University of Northumbria Business School. Weitere Engagements bei Continental und Henkel.

Schwerpunkte: Interkulturelle Kommunikation, Diversity Management, Gender, Austausch Deutschland/USA, Organisationsentwicklung, Dialogprozess, Systemtheorien

idm-Mitglied seit 2003, bis 2008 idm-Vorstandsmitglied, Mitglied des idm-EU-Diversity-Projekts 2007-2008

von Dr. Stephen Holmes

The more we investigate culture and communication the more complex they become. The more complex and diverse reality becomes the more uncertain and anxious people become as they proceed to decide and act in their daily lives. People are faced with decisions and paths of action in global and local contexts of increasing diversity; inspite of increasing complexity managers and leaders have to reduce and converge onto one course of action. This article is meant as a small contribution to clarifying this contradiction between complexities (or diversities) and the need for their reduction, as it is expressed in two forms of training in organizations, intercultural communication (IC) and dialogue process. More specifically, how and to what extent can clarification of some basic terms in intercultural communication (Bennett 1993 & 1998, Dodd 1998, Casmir 1999, Hall 1966 & 1998, Marten & Nakayama 2000, etc.) and dialogue process (Bohm 1996, Ellinor & Gerard 1998 & 2001, Hartkemeyer, Hartkemeyer & Dhority 1998, Isaacs 1999, Simmons 1999) contribute to the synthesis of these two approaches?

I am making three important assumptions in this inquiry: 1) Clarification is central but it has to stay in a productive relationship to its opposite, the lack of it (chaos, perturbations, vagueness, processes). This is necessary to avoid reification of the terms in question and to allow for creative space. 2) An example of this necessary lack of clarity can be found in much of mainstream IC in the US in their assumption that the difference between intercultural communication and diversity management is simply not an issue. Once one focuses on communication style as a major category, then clarity of the differences between national cultures and, for example, gender, ethnic minorities, personalities and histories are just not very important, thus consequently are less likely to be reified. (When given unlabelled descriptions, for example, of an African-American and an Anglo-American communication style to European trainees or students, they will inevitably guess these are two national cultures.) A carefully prepared description of a communication style or company culture in a specific context, from the standpoint of pragmatics, is much more useful than, for example, generalities about whether the Americans are more individualistic than the Germans in their ways of doing business. 3) Finally, synthesis is simply the theoretical correlation to synergy, which is more a reference to practice. The focus on sythesis in this article is meant to stimulate the generation of new forms of practice.

As a consequence, the first task of this article is to clarify the terms intercultural communication (IC), "Third Culture" (TC) and communication style. The second task will be to describe and elucidate dialogue theory and certain aspects of its practice in light of some possible fruitful connections to IC. Part of the discussion will be the examination of the utility of constructing dialogue styles as well as diverse cultural, gender, ethnic or personal communication styles, all of which can exist at the same time in actual experience.

Understanding intercultural communication as a discipline starts with the question of the definitions of culture and communication.

There seem to be endless definitions of culture and, consequently, in the spirit of Occam's razor, I'll divide the definitions of culture into three areas, the last of which will be the working definition for this paper.

a. The first definition of culture is the most common view that people are used to (at least in Western Europe and the US); it is something that either people have or they don't. In anthropology this use of the word culture refers to the presence of a "high culture" and is therefore elitist. It implies an appreciation of a certain aesthetic niveau, a specialization of the sphere of culture, which is separate from other spheres such as politics and economics.

b. The second direction of definitions arose historically out of cultural anthropology. Such definitions either comprise long lists of contents or aspects of culture such as habits, traditions, law, morals, norms, rituals, etc., or they are referred to as patterns of behavior which are learned or acquired in our socialization. Sometimes the term "system" appears in the definitions, sometimes not. But normally the proponents of these definitions equate cultures with identifiable wholes which can be described and compared systematically. This has nearly always been tacitly assumed and not questioned.

c. In the last 35 years that has changed. The charge of reification and reduction has reverberated many times from the side of the critics. Take the words of the cultural anthropologist, Clifford Geertz (1973: 11):

One is to imagine that culture is a self-contained "superorganic" reality with forces and purposes of its own, that is, to reify it. Another (way to imagine it, S.H.) is to claim that it consists in the brute pattern of behavioral events we observe in fact to occur in some identifiable community or other; that is, to reduce it.

Geertz' criticism is on the level of reified objectivity; on the subjective level he is just as critical in his reference to Ward Goodenough's view of culture "in the minds and hearts of men." (in Geetz, 1973: 11)

Geertz offers an alternative "interpretive view of culture"; "we begin with our own interpretations of what our informants are up to, or think they are up to, and systematize" them by putting them into writing. These writings are "constructions" or "fictions", not false as such, but rather "'as if' experiments." (1973: 11) He emphasizes that "cultural analysis is intrinsically incomplete. And...the more deeply it goes the less complete it is." (1973: 29) One major consequence of this statement by Geertz is that culture does not have to be a system, but it can be , through conscious or subconscious construction. National and company cultures, for example, at least in the beginning are consciously, and later subconsciously constructed and maintained as the generations pass. If a company culture is having problems with its diversity mosaic, then it follows that its participants have to become fully conscious of what their company culture is, including its systemic character, and how it relates to its environment. It further follows logically that the observation and self-observation of a company culture is not to be taken lightly. (Notice I did not say analysis. Analysis comes after observation. Observation, including all receptive skills, is a difficult, complex activity, to be checked and double-checked again and again.)

Edward Hall (1998: 54-55), the founder of intercultural communication as a discipline, once made a distinction between two aspects of culture: "manifest" and "tacit acquired". By "manifest" culture he meant "words and numbers"; by "tacit acquired" he meant the nonverbals of communication, that which is "highly situational and operates according to rules which are not in awareness, not learned in the usual sense but acquired in the process of growing up or simply being in different environments." He mentioned that his studies of this aspect of culture "grew out of the study of transactions at cultural interfaces. The study of an interface between two systems is different than from the study of either system alone. (W)orking at the interfaces has proved fruitful because contrasting and conflicting patterns are revealed." In this paper I want to continue Hall's use of the term "interface", which in my view, should be central vocabulary for talking about communication and culture. "Culture is communication." (53) Culture is what happens at the interface to the diverse "other", both verbally and nonverbally. This nonverbal emphasis in the study of culture cannot be underestimated in its significance for Hall meant it to be a pathway to the subconscious. (He maintained explicitly that his studies of nonverbal communication are the key to understanding Gregory Bateson's idea of the double bind.) The deepest levels of culture are subconscious, implying that the study of nonverbal communication can lead us to these deep levels. The practical question deriving from this study is: How can we make the subconscious conscious and thereby turn it into a management tool, in order to send and receive messages more effectively across interfaces?

Generally speaking, communication is a form of social interaction; another form of social interaction is operationalization. As in communication, people send and receive messages across interfaces in other forms of social interaction, that is, across the operational interfaces with their bodies and their environments. Interfaces with the body must be taken seriously; awareness and mindfulness of the processes in the body (including thinking, feeling, and awareness of the senses, attention and focus) and their interfaces with the environment, have to be practiced constantly. (Remember the choreographer in the film "Rhythm is it".) Our "natural" habits of focussing our attention and perception and how these relate to our thinking are our subjective culture. To go beyond the "natural", dialogue process can be of great help. It is beyond these "natural" ways of doing things where innovation, creativity and synergy begin.

A major area of discussion within intercultural communication involves the question as to the usefulness of the socalled "Third Culture" model. Two interculturalists will be referred to here: Carley Dodd (1998) and Fred Casmir (1999). The main reason for choosing this model as a topic in this paper is that efforts are already underway to use it as a generator of forms of training and to bring together the applications from this model and from those of the dialogue process. (See Matoba)

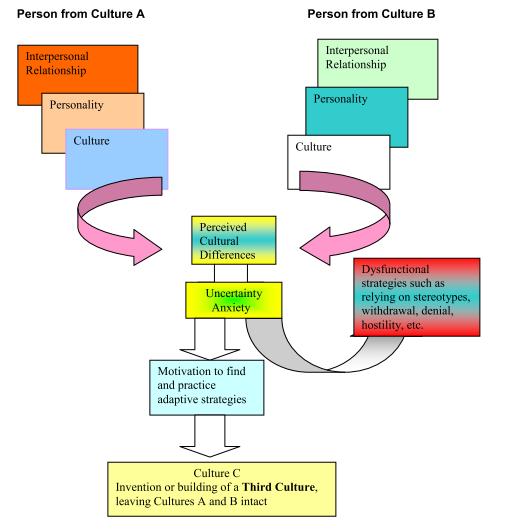

Figure 1: Third Culture Frame or Model (Adapted from Carley Dodd 1998: 6)

The "Third Culture" (TC) model starts with imagining that a person from culture A meets a person from culture B. They both notice differences and uncertainty and ideally both start to build culture C based on a new combination of contrasts and similarities. Culture C is the Third Culture which is constructed in some way by both or all parties involved in the attempt at communication or cooperation. As in Figure 1, according to Dodd, the persons from cultures A and B are not just from cultures alone. They are more than that. Each person is intimately related to culture, personality and an interpersonal relationship. (Dodd 1998: 6-8) This point is significant because often the differences between these aspects of consciousness are separated, reified, overly exaggerated and compartmentalized.

We can extract two strengths from Dodd's model:

1) it allows for the complexity and points toward increasing complexity and 2) it transcends culture by pointing to personality and relationship levels, thereby approaching the broader concept of diversity. Rather than talking about intercultural communication, diversity communication is closer to what is really going on in the communication process. Diversity as such is the better term because it does not limit itself to the cultural nor to the personal. (Furthermore, it is easier to integrate into evolutionary theory.)

Dodd uses some other elements in his model. When the first and second cultures come together, he introduces the construct of "perceived cultural differences (PCDs)" (1998: 6-8). Perception becomes a major part of his theory in the basic assumption that all cultural and personal differences are mediated through perception. (Often in Germany in their discussions of culture and systems, little attention is given to perception; thinking, analysis and action have priority. This topic, however, deserves another article and will not be dwelled upon here.)

The next step in the model is that the PCDs can lead to "uncertainty" and "anxiety", the cognitive and emotional sides of the same coin. From there the reaction on the part of the participants can be either functional or dysfunctional strategies for coping with the situation. Dysfunctional includes strategies such as "stereotyping, withdrawal, denial and hostility". On the more functional level the participants are motivated to find adaptive, more positive paths for providing "for a common ground for relationship-building strategies." The model "underscores how we can utilize several simple but powerful intercultural insights and skills" which can bring about desired outcomes. "In sum, the model is an adaptive model, calling for participants to suspend judgement (emphasis by SH) and bias while they engage in a third culture created by the intercultural participants to explore mutual goals and common concerns. In other words, out of the perception of differences, participants A and B can carve out a Third Culture between them, a culture of similarity." (1998: 6-10) For now let us note that suspending judgement is a key skill proposed by Dodd to build a Third Culture. It is also a key skill in the dialogue training.

Fred Casmir gives a very elaborate argument for the use of the Third Culture model. He maintains the TC is a "construction of a mutually beneficial interactive environment in which individuals from two different cultures can function in a way beneficial to all involved"; it is "communication-centered" and focuses on "long-term building processes." (1999: 92). One strength here for our purposes is that Casmir focuses much more on the environment in which the building of the Third Culture takes place. (For a bridge one needs an environment and a sense of space and time.) Relying on chaos theory Casmir tries to move away from the assumption that a culture is somehow a system with a stable identity; he understands it "not as an endstate but as an ongoing evolutionary process." (1999: 95)

This assumption concerning chaotic systems contradicts some of mainstream intercultural communication in its application in business environments, in particular, the work of Gert Hofstede (1997), who begins with universal, etic dimensions of culture and universal definitions of these dimensions; this sort of interculturalist then proceeds to measure the presence or absence of these dimensions in national cultures (presumably stable identities). Nigel Holden (2002: ch. 2) criticizes Hofstede in the same spirit as Geertz criticizes mainstream uses of the term culture. Instead of quantifying the degrees of presence or absence of universal dimensions, Holden advocates the collection and study of "thick" descriptions of companies and their identities as they struggle with the intercultural barriers and challenges of globalization. The study of "thick" descriptions of organizational identities, very much like in ethnography, should lead to an accumulation of experience and knowledge which a company can use effectively as a competitive advantage. (2002: ch. 5, especially 95-99)

The term communication style is drawn from the discipline of intercultural communication and understood as a recognizable set of communication patterns (See Alexander 1979 for an attempt at creating a pattern language in architecture.). By necessity, communication styles cannot be considered hard facts; they are rather "loose" as in the patterns in a piece of art or music, nevertheless, empirical and observable. Patterns, however, also have limits. A painting has the limits of its frame and materials; a piece of music has limits in a score or a theme as well as the acoustics of the setting; both art and music are limited by the performers' abilities. The painting or the performance, however, is what communication is all about. A score without a performance is dead; a performance without a score is conceivable (ex. Jazz), but without a style it is inconceivable. There must be patterns in any piece of art or music and a style is recognized on the basis of patterns.

A communication style, consequently, can be depicted as a set of patterns with limits and these limits indicate a frame. Just as a person's interest, experience and her study of painting can enhance the understanding of it, so the interest, experience and study of communication styles as frames can improve the likelihood of an expanding understanding and more coherent communication and dialogue. Examples of communication styles might be in relation to gender: separate (more male) and connected (more female) (Belinky, et.al., 1997: ch. 6). There might be a German (Nies, 2000: ch. 4), American (Stewart & Bennett, 1991: ch. 8), or Japanese (Barnlund, 1989) communication style, along the lines of national culture. And finally dialogue and discussion/debate, as will be described later by Ellinor and Gerard, can be considered communication styles. Furthermore, if people become aware of these different styles, then they can practice applying them to their relevant situations and contexts as well as relevant interfaces of culture, co-culture, gender, age, professional cultures, company cultures, etc. If they are aware of the limits of these situations, contexts and interfaces, then they can better determine their range of choices. If one particular style, in this case, dialogue, already has built into it the stretching of the communicative space and time, it can also help people to stretch the limits and thereby include a wider than usually expected range of choices. I argue that there is something special about dialogue process; it is not just one of the many styles (national, gender, etc.) It can be applied in order to improve the communication, especially when the diversity of the "other" increases. It is the only communication style which consciously focuses on understanding the complexities and paradoxes of the social interaction, and on conscious stretching of ritual space and time.

To make it more complex but realistic, communication and operational styles may be embedded in numerous organizational contexts like meetings, interviews, presentations, negotiations, buying/selling, planning, conflict resolution, explaining procedures, describing processes, talking about trends and statistics, small talk, etc. A context, as Deborah Tannen (1994: 15) in her gender studies of the American workplace utilizes effectively in her research, can also be a ritual context; she is interested in the "'ritual' character of interaction."

To appreciate our perception and experiences of cultural communication patterns, someone needs to record them and implant them into an extended memory (like writing or a score, or the piece of art). When people collect the rich intercultural experience and gain recognition of cultural patterns, take these patterns and connect them up into larger patterns, then these larger patterns at some point become a communication style. When extended descriptions are recorded, when the observer deepens her/his description, then "thick" descriptions are the result (Again, see Holden 2002: 95-98). From a business point of view, these descriptions become a source of knowledge which can help a company store, pass on and improve on its intercultural knowledge from generation to generation of their managers and staff. Holden's method is based on the careful selection of relevant, learning experience and organizational cultural patterns of a company. These relevant company cultural patterns can be woven together to create company cultural communication and operational styles. As styles take on firmer borders for the sake of recognition and application, they acquire a framelike character, thus the term frame. But here I emphasize that a frame or style must remain open to learning as much as possible to allow for the input from the side of the informants of new developments and new knowledge. In order to allow for more learning and input, dialogue process is a more than adequate tool.

Dialogue process here is conceptualized from the attempts in the last few years in California (Glenna Gerard and Linda Ellinor) and at MIT (William Isaacs) to develop synergy in organizations. Both were inspired by David Bohm's book On Dialogue (1996). Near the end of his life, Bohm, an accomplished Nobel Prize winner in physics and a creative philosopher of science, felt that there was a disparity between insights from modern science and social communication. His last short book on dialogue was meant to reconcile this disparity. Organizational developers like Peter Senge and William Isaacs at MIT and two consultants from the west coast, Glenna Gerard and Linda Ellinor, were inspired to find ways to put Bohm's theory into practice. Peter Senge (1990: ch.12) was hoping that dialogue as a practice could compliment his own theory and practice in what is called Learning Organization. Out of this search for forms of practice which could be applied to organizations, numerous tools and skills have been recognized, developed and tested in the dialogue process. The lists of skills and behaviors being practiced vary but they certainly are not as long as the numerous skills listed by the interculturalists, e.g. at the end of each chapter of Dodd (1998). Reducing the lists, again in the spirit of Occam's razor, and connecting up the skills logically (approaching a grammar) can be of great significance for practice.

Dialogue has many facets. Chapter one of Bohm's little book (1996) is entitled "On Communication." He maintains that implicit in the communication process is the experience of difference and similarity. "In such a dialogue, when one person says something, the other person does not in general respond with exactly the same meaning as that seen by the first person. Rather, the meanings are only similar and not identical. Thus, when the second person replies, the first person sees a difference between what he meant to say and what the other person understood. On considering this difference, he may then be able to see something new, which is relevant both to his views and to those of the other person." (Bohm, 1996: 2) Notice the similarities of this view to some of the assumptions about practicing intercultural competence. Following the Third Culture model, the first step in attaining such a competence is to recognize the differences which then supply the intercultural contrasts necessary to start the search for similarities. Both disciplines view communication as central and both disciplines highlight the creative tension between perceiving differences and similarities.

Linda Ellinor and Glenna Gerard define dialogue in terms of a contrast between dialogue and discussion/debate, called appropriately "The Conversation Continuum" (2001: 2). Both of these, dialogue and discussion/debate, have appropriate contexts and situations for their application and both have their strengths and weaknesses. To see them as a continuum allows for shades which may be difficult to place on one side or the other. In this contrast between dialogue and discussion/debate another entry point to intercultural communication becomes visable. That is, both can be considered communication styles with different basic assumptions about reality. From both, the observer can detect different conversation patterns.

| Dialogue | Discussion/Debate |

| Seeing the whole among parts | Breaking issues/problems into parts |

| Seeing the connections between parts | Seeing distinctions between parts |

| Inquiring into assumptions | Justifying/defending assumptions |

| Learning through inquiry and disclosure | Persuading, selling, telling |

| Creating shared meaning | Gaining agreement on one meaning |

Different nonverbals can be expected as well (ex. receptive gestures and body position vs combative gestures and body position, eye contact, the role of silence, ritual context, etc.) and when the nonverbals become theoretically just as important as the verbals, then we have arrived at Hall's contribution to intercultural communication. Participants within a particular culture, profession, ethnic group, gender, etc. may not notice that their particular kind of debate or dialogue is colored by their basic assumptions and experiences arising from their diverse cultural and co-cultural backgrounds. In the spirit of Deborah Tannen's (1994) proposing different gender communication styles (at least in America), a group of women dialoging may be confusing it with "sharing", being very personal and sympathetic, smoothing the rough edges of the flow of conversation, etc. The implication here is that not only may there be different cultural and personal communication styles, there may also be different dialogue styles (See Matoba). Keeping this in mind can lead to an enrichment of both dialogue process and intercultural communication.

Ellinor and Gerard, in their attempt at an introduction to dialogue and its applications in organizations, list five skills. (2001: 2-3)

1. Suspension of Judgement

2. Listening

3. Reflection

4. Assumption Identification

5. Inquiry

These five skills fit neatly into a structured whole, in a grammatical sense. A major basic assumption for this communicative, social interactive whole is that a person (people) cannot not judge, think or communicate. If this assumption is true, then the precondition for people coherently thinking, communicating or operating together is to be able to "observe", experience or perceive their own judging, feeling and thinking processes. (This was what Bohm meant by proprioception, the ability to be aware of one's bodily processes - including thinking and feeling.)

Ellinor and Gerard maintain that "suspension of judgement, a skill key to dialogue, isn't about stopping judging - we couldn't do that if we tried. Rather, it's about noticing what our judgements are and then holding them lightly so we can still hear what others are saying, even when it may contradict our judgements." (2001: 7). By suspending our judgements, feelings and thoughts we can create mental space to recognize our own basic assumptions and values, to continue to listen and enquire in order to understand the other and the whole interaction. All of this movement presupposes that the person dialoging moves into the metacognitive position of observing the observer. Reflection is part of this self-observation. When people reflect, they ideally "observe" their memories in a slow, relaxing process. People can reflect on what happened in an interaction two hours ago in which they got very angry about something which really in hindsight was not all that important. By focusing on their anger they can assume that some deep assumption or value was violated. Through further reflection on the source of their anger and the perceived violation, they can discover a deep assumption or value. Once they ask themselves where they got a value, then they have to recall their biographies and what they learned from their parents, school, church, etc. Such a path of reflection can help them arrive at some insight into their cultural selves, a precondition for understanding the cultural or personal "other".

Let us summarize some of the points of merging of the two forms of training.

First, clarification of the terms of IC can be helpful for mutual complimenting of IC and dialogue process. Culture understood as communication or what happens at the interface does not have to be a system, but it can be. People contruct their systems. If they can become conscious of how they created and continue to create and maintain, for example, their company or national cultures and identities, then they can creatively modify these cultures and identities. Diversity management can only be successful in the long run, if managers of organizations think and act on such meta-levels.

The Third Culture model gives managers a simple tool for dealing effectively with the cultural, personal and relational other. It centers in on functional and dysfunctional attempts at reciprocal adaptation of people from cultures A and B. If the attempt is functional and successful, then a Culture C or Third Culture is the result. The fact that Dodd focuses on aspects of the person which are beyond culture lends to the recommendation that diverse communication is a better scientific term than intercultural communication. Dodd also highly recommends the skill of suspending judgement, a primary skill practiced in the dialogue training. By including the environment and by emhasizing culture as a construction in process (without a necessary, given endstate), Casmir brings the model closer to systems and chaos theory.

The attempt at creating national cultural, gender and other communication styles based on synthesizing observed patterns of interaction is a potentially fruitful source of practice. Observation and the receptive skills are taken very seriously, as in Holden's advocating the collection of thick descriptions as sources of cultural knowledge for companies. Dialogue and discussion/debate can be considered communication styles. Like a constructed national culture or company culture, they have deep tacit assumptions which are critical to maintaining the style. Dialogue, however, has a special status. It is the only communication style which consciously tries to comprehend wholes and to stretch those wholes to include more conflicting viewpoints. Dialogue can help to frame and reframe itself and other communication styles for pragmatic purposes and therefore support the decision making of managers.

Second, when a person recognizes her own and other's (or others') deep, basic assumptions in the communication process, she has taken the first step toward recognizing, with continuing reflection and inquiry, the cultural and personality aspects of those assumptions. Dialogue can help change the implicit into the explicit, the subconscious into the conscious. Such competence is absolutely crucial for diversity management (or for any kind of management which has to deal in some way with increasing diversity).

Third, mindfulness of nonverbal communication, equal to the verbal, is a key discovery of Edward Hall, the founder of intercultural communication. Part of its significance is that it allows us access to the subconcious aspects of our culture and our individual histories. We now have two tools, one from dialogue and one from IC; both can help us become aware of our subconscious identities as individuals and as groups. (This is of major importance to understanding one's company culture!)

Fourth, both interculturalists (like Dodd) and dialogue trainers place a major focus on practicing certain skills like suspending judgement. Dialogue competence reduces the length of the list of skills, a common complaint of the discipline of intercultural communication. Dialogue is closer to the principle of Occam's razor; however, without the input from intercultural communication, it will often be trapped in ethnocentrism. Dialogue as a communication style can never be separated in a reified way from other communication styles like national cultural, gender, personal, etc. Also, for pragmatic purposes, especially in business organizations, it has to be in a supporting relationship to its opposite, discussion and debate. At some point, decisions have to be made and people need to act, in the context of the organizational culture. Culture does not have to have a system but organizational cultures normally do. They were and are being created systematically, based on their success; otherwise, they tend to break down, which is also a common occurence.

In conclusion, much work needs to be done on understanding how dialogue process and the discipline of intercultural communication - here I include diversity management and operations - can co-enhance one another. This article was only meant to stimulate people to think about and to experiment with new paths of training and action.

Dialogue can be a creative, powerful ritual, also including different communication and operational styles related to culture and diversity. Consequently, these different particular cultural styles can influence the total style of the dialogue, implying a higher metacognitive level than before. One such level to be reached by managers and leaders is that from which they can observe or recognize differences in cultural communication styles. If American white women come together and dialogue, one can expect the dialogue style to be influenced by the women's communication style. If Germans come together to dialogue, they will most likely form a German style of dialogue based on their German style of communication. Kazuma Matoba from Witten/Herdecke University can distinguish differences in dialogue styles in Japan, Germany and Namibia. (See also his article in this collection.) The ability to observe this jump from a lower (culture or dialogue) to a higher meta-level (culture and dialogue) can lead to an improvement of both intercultural and dialogue competence and diversity management.

Alexander, Christopher (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barnlund, Dean C. (1989). Communicative Styles of Japanese and Americans. Belmont, California: Wadsworth.

Belinky, Mary Field; Clinchy, Blythe McVicker; Goldberger, Nancy Rule; Tarule, Jill Mattuck. (1997). Women's Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind. (10th. Anniversary Ed). New York: Basic Books

Bennett, Milton (1998), "Intercultural Communication: A Current Perspective", Milton Bennett (ed). Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication. Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press, pp. 1-34.

Bennett. Milton (1993). "Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity," Education for the Intercultural Experience ( Ed). R. Michael Paige (ed.), Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press.

Bohm, David. (1996). On Dialogue. Ed. Lee Nichol. London & New York: Routledge.

Bohm, David and Peat, David. (1987). Science, Order, and Creativity. (2nd Ed). London & New York: Routledge.

Casmir, F.L. (1999). "Foundations for the Study of Intercultural Communication based on a Third-Culture Model," Intercultural Rela- tions. Vol. 23, Nr 1, Jan. pp. 91-116.

Dodd, Carley H. (1998). Dynamics of Intercultural Communication (5th Ed). Boston, et.al.: McGraw-Hill.

Ellinor, Linda and Gerard, Glenna (2001). Dialogue at Work: Skills at Leveraging Collective Understanding. Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications

Ellinor, Linda and Gerard, Glenna. (1998). Dialogue: Creating and Sustaining Collaborative Partnership at Work, Rediscovering the Transforming Power of Conversation. New York: Wiley & Sons.

Geertz, Clifford. (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. No City: Perseus.

Hall, Edwart T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. New York: Anchor/Doubleday.

Hall, Edward T. (1998) "The Power of Hidden Differences," in Milton Bennett (ed). Basic Concepts of Intercultural Com- munication: Selected Readings. Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press, pp. 53-67.

Hall, Edward T. (1959). The Silent Language Greenwich. CN: Faucett.

Hartkemeyer, Martina; Hartkemeyer, Johannes F. and Dhority, Freeman. (1998). Miteinander Denken: Das Geheimnis des Dialogs. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Hofstede, Geert. (1997). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York, et.al.: McGraw-Hill.

Holden, Nigel. (2002). Cross-Cultural Management: A Knowledge Perspective. Harlow, England, et.al.: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Isaacs, William. (1999). Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together: A Pioneering Approach to Communicating in Business and in Life. New York, et.al.: Currency

Martin, Judith N. & Nakayama, Thomas K. (2000). Intercultural Communication in Contexts (2nd Ed). London & Toronto: Mayfield.

Matoba, Kazuma (2003-2006) Witten/Herdecke University (Germany), Personal Communication and Professional Cooperation over these Years (Contact through his email address: kazuma.matoba@uni-wh.de )

Nees, Greg. (2000). Germany: Unraveling an Enigma. Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press.

Senge, Peter M (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization: New York, London, et.al.: Double-day/Currency.

Simons, Annette (1999). A Safe Place for Dangerous Truths: Using Dialogue to Overcome Fear & Distrust at Work. New York, et.al.: American Management Association

Stewart, Edward C. & Bennett, Milton (1991). American Cultural Patterns: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. (2nd. Ed). Yarmouth, Maine: Intercultural Press.

Tannen, Deborah.(1994). Talking from 9 to 5: How Women's and Men's Conversational Styles Affect Who Gets Heard, Who Gets Credit, and What Gets Done at Work. New York: William Morrow